July

21 2018, 5:17 p.m.

Photo: Niklas Halle'n/AFP/Getty

Images

ECUADOR’S PRESIDENT Lenin Moreno traveled to London on Friday

for the ostensible purpose of speaking at the 2018 Global Disabilities Summit (Moreno has been using a

wheelchair since being shot in a 1998 robbery attempt). The concealed,

actual purpose of the President’s trip is to meet with British officials to

finalize an agreement under which Ecuador will withdraw its asylum protection

of Julian Assange, in place since 2012, eject him from the Ecuadorian Embassy

in London, and then hand over the WikiLeaks founder to

British authorities.

Moreno’s itinerary also notably

includes a trip to Madrid, where he will meet with Spanish officials still seething over Assange’s denunciation of human rights

abuses perpetrated by Spain’s central government against protesters

marching for Catalonia independence. Almost three months ago,

Ecuador blocked Assange from accessing the internet, and Assange has not

been able to communicate with the outside world ever since. The primary factor in Ecuador’s decision to silence him was Spanish

anger over Assange’s tweets about Catalonia.

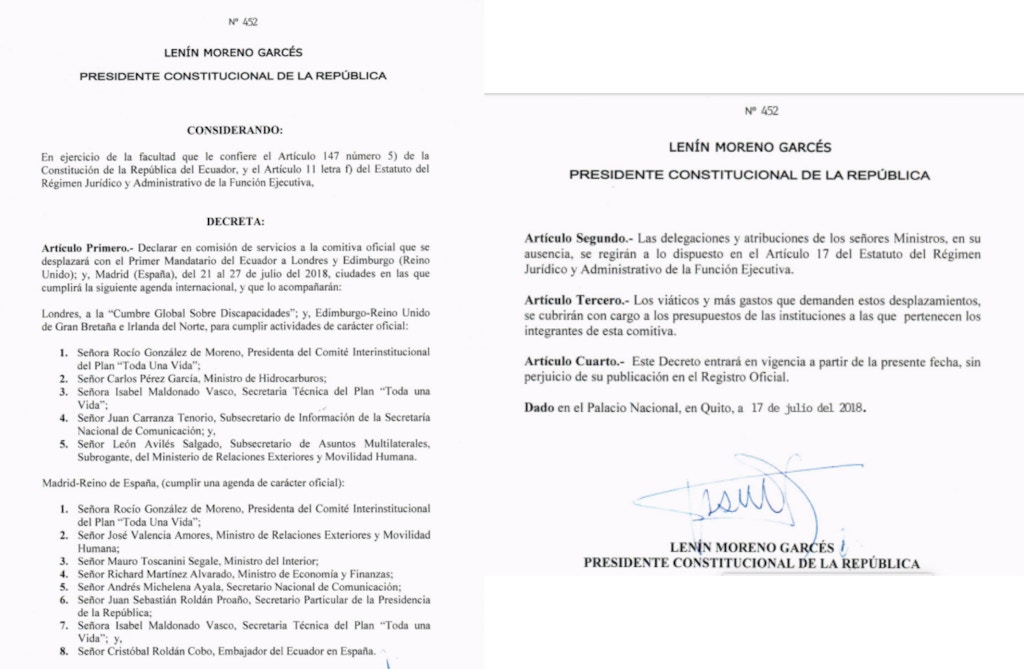

Presidential decree signed on July 17

by Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno, outlining his trip to London and Madrid

A source close to the Ecuadorian

Foreign Ministry and the President’s office, unauthorized to speak publicly,

has confirmed to the Intercept that Moreno is close to finalizing, if he has

not already finalized, an agreement to hand over Assange to the UK within the

next several weeks. The withdrawal of asylum and physical ejection of Assange

could come as early as this week. On Friday, RT reported that Ecuador was preparing to enter into such an

agreement.

The consequences of such an agreement

depend in part on the concessions Ecuador extracts in exchange for withdrawing

Assange’s asylum. But as former Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa told the Intercept in an interview in May, Moreno’s government has

returned Ecuador to a highly “subservient” and “submissive” posture toward

western governments.

It is thus highly unlikely that

Moreno – who has shown himself willing to submit to threats and coercion from

the UK, Spain and the U.S. – will obtain a guarantee that the U.K. not

extradite Assange to the U.S., where top Trump officials have vowed to prosecute

Assange and destroy WikiLeaks.

The central oddity of Assange’s case

– that he has been effectively imprisoned

for eight years despite

never having been charged with, let alone convicted of, any crime – is

virtually certain to be prolonged once Ecuador hands him over to the U.K. Even

under the best-case scenario, it appears highly likely that Assange will continue

to be imprisoned by British authorities.

The only known criminal proceeding

Assange currently faces is a pending 2012 arrest warrant for “failure to

surrender” – basically a minor bail violation that arose when he obtained

asylum from Ecuador rather than complying with bail conditions by returning to

court for a hearing on his attempt to resist extradition to Sweden.

That offense carries a prison term of three months and a fine, though it

is possible that the time Assange has already spent in prison in the UK could

be counted against that sentence. In 2010, Assange was imprisoned in Wandsworth Prison, kept in isolation, for 10 days until he was released

on bail; he was then under house arrest for 550 days at the home of a

supporter.

Assange’s lawyer, Jen Robinson, told

the Intercept that he would argue that all of that prison time already served

should count toward (and thus completely fulfill) any prison term imposed on

the “failure to surrender” charge, though British prosecutors would almost

certainly contest that claim. Assange would also argue that he had a

reasonable, valid basis for seeking asylum rather than submitting to UK

authorities: namely, well-grounded fear that he would be extradited to the

U.S. for prosecution for the act of publishing documents.

Beyond that minor charge, British

prosecutors could argue that Assange’s evading of legal process in the UK was

so protracted, intentional and malicious that it rose beyond mere “failure to

surrender” to “contempt of court,” which carries a prison term of up to two years. Just on those charges alone,

then, Assange faces a high risk of detention for another year or even

longer in a British prison.

Currently, that is the only known

criminal proceeding Assange faces. In May, 2017, Swedish prosecutors announced they were closing their investigation into the sexual

assault allegations due to the futility of proceeding in light of

Assange’s asylum and the time that has elapsed.

THE FAR MORE IMPORTANT question that will determine Assange’s future is

what the U.S. Government intends to do. The Obama administration was eager to

prosecute Assange and WikiLeaks for publishing hundreds of thousands of

classified documents, but ultimately concluded that there was no way to do so without either

also prosecuting newspapers such as the New York Times and the Guardian which

published the same documents, or create precedents that would enable the

criminal prosecution of media outlets in the future.

Indeed, it is technically a crime

under U.S. law for anyone – including a media outlet – to publish certain types

of classified information. Under U.S. law, for instance, it was a

felony for the Washington Post’s David Ignatius to report on the contents of telephone calls, intercepted by the NSA,

between then National Security Adviser nominee Michael Flynn and Russian

Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, even though such reporting was clearly in the

public interest since it proved Flynn lied when he denied such contacts.

That the Washington Post and Ignatius

– and not merely their sources – violated U.S. criminal law

by revealing the contents of intercepted communications with a Russian

official is made clear by the text of 18 § 798 of the U.S. Code, which provides (emphasis added):

“Whoever knowingly and willfully

communicates … or otherwise makes available to an unauthorized

person, or publishes … any classified information … obtained

by the processes of communication intelligence from the communications of any

foreign government … shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more

than ten years, or both.”

But the U.S. Justice Department has

never wanted to indict and prosecute anyone for the crime of publishing such

material, contenting themselves instead to prosecuting the government sources

who leak it. Their reluctance has been due to two reasons: first, media outlets

would argue that any attempts to criminalize the mere publication of classified

or stolen documents is barred by the press freedom guarantee of the First

Amendment, a proposition the DOJ has never wanted to test; second, no

DOJ has wanted as part of its legacy the creation of a precedent that

allows the U.S. Government to criminally prosecute journalists and media

outlets for reporting classified documents.

But the Trump administration has made

clear that they have no such concerns. Quite the contrary: last April, Trump’s

then-CIA Director Mike Pompeo, now his Secretary of State, delivered a deranged, rambling,

highly threatening broadside against WikiLeaks. Without citing any evidence,

Pompeo decreed that WikiLeaks is “a non-state hostile intelligence service

often abetted by state actors like Russia,” and thus declared: “we have to

recognize that we can no longer allow Assange and his colleagues the

latitude to use free speech values against us.”

The long-time right-wing Congressman,

now one of Trump’s most loyal and favored cabinet officials, also explicitly

rejected any First Amendment concerns about prosecuting Assange,

arguing that while WikiLeaks “pretended that America’s First Amendment

freedoms shield them from justice . . . they may have believed that, but they

are wrong.”

Pompeo then issued

this bold threat: “To give them the space to crush us with

misappropriated secrets is a perversion of what our great Constitution stands

for. It ends now.”

Trump’s Attorney General Jeff

Sessions has similarly vowed not only to continue and expand the Obama

DOJ’s crackdown on sources, but also to consider the prosecution of media

outlets that publish

classified information. It would be incredibly shrewd for Sessions to lay

the foundation for doing so by prosecuting Assange first, safe in the knowledge

that journalists themselves – consumed with hatred for Assange due to personal

reasons, professional jealousies, and anger over the role they believed he

played in 2016 in helping Hillary Clinton lose – would unite behind the

Trump DOJ and in support of its efforts to imprison Assange.

During the Obama years, it was a

mainstream view among media outlets that prosecuting Assange would be a serious

danger to press freedoms. Even the Washington Post Editorial Page, which

vehemently condemned WikiLeaks, warned in 2010 that any such prosecution would “criminalize the

exchange of information and put at risk” all media outlets. When Pompeo and

Sessions last year issued their threats to prosecute Assange, former Obama DOJ

spokesperson Matthew Miller insisted that no such prosecution could ever

succeed:

For years, the Obama DOJ searched for

evidence that Assange actively assisted Chelsea Manning or other sources in the

hacking or stealing of documents – in order to prosecute them for more

than merely publishing documents – and found no such evidence. But even that

theory – that a publisher of classified documents can be prosecuted for

assisting a source – would be a severe threat to press freedom, since

journalists frequently work in some form of collaboration with

sources who remove or disclose classified information. And nobody has ever

presented evidence that WikiLeaks conspired with whomever hacked the DNC and

Podesta email inboxes to effectuate that hacking.

But there seems little question that,

as Sessions surely knows, large numbers of U.S. journalists – along with many,

perhaps most, Democrats – would actually support the Trump DOJ in prosecuting

Assange for publishing documents. After all, the DNC sued WikiLeaks in April for

publishing documents –

a serious, obvious threat to press freedom – and few objected.

And it was Democratic Senators such as Dianne Feinstein who, during the Obama years, were urging the

prosecution of WikiLeaks, with the support of numerous GOP Senators. There is no doubt that, after 2016, support among

both journalists and Democrats for imprisoning Assange for publishing documents

would be higher than ever.

IF THE U.S. DID INDICT Assange for alleged crimes relating to the

publication of documents, or if they have already obtained a sealed indictment,

and then uses that indictment to request that the U.K. extradite him to

the U.S. to stand trial, that alone would ensure that Assange remains in

prison in the U.K. for years to come.

Assange would, of course, resist any

such extradition on the ground that publishing documents is not a cognizable

crime and that the U.S is seeking his extradition for political charges that,

by treaty, cannot serve as the basis for extradition. But it would take at

least a year, and probably closer to three years, for U.K. courts to

decide these extradition questions. And while all of that lingers, Assange would

almost certainly be in prison, given that it is inconceivable that a British

judge would release Assange on bail given what happened the last time he was

released.

All of this means that it is highly

likely that Assange – under his best-case scenario – faces at

least another year in prison, and will end up having spent a decade in

prison despite never having been charged with, let alone convicted of, any

crime. He has essentially been punished – imprisoned – by process.

And while it is often argued that

Assange has only himself to blame, it is beyond doubt, given the Grand Jury convened by the Obama DOJ and now the threats of Pompeo and Sessions, that

the fear that led Assange to seek asylum in the first place – being

extradited to the U.S. and politically persecuted for political crimes – was

well-grounded.

Assange, his lawyers and his

supporters always said that he would immediately board a plane to Stockholm if

he were guaranteed that doing so would not be used to extradite him to the

U.S., and for years offered to be questioned by Swedish investigators inside

the embassy in London, something Swedish prosecutors only did years

later. Citing those facts, a United Nations panel ruled in 2016 that the actions of the U.K. government

constituted “arbitrary detention” and a violation of Assange’s fundamental

human rights.

But if, as seems quite likely,

the Trump administration finally announces that it intends to prosecute

Assange for publishing classified U.S. Government documents, we will be faced

with the bizarre spectacle of U.S. journalists – who have spent the last two

years melodramatically expressing grave concern over press freedom due to

insulting tweets from Donald Trump about Wolf Blitzer and Chuck Todd or his

mean treatment of Jim Acosta – possibly cheering for a precedent that would be

the gravest press freedom threat in decades.

That precedent would be one that

could easily be used to put them in a prison cell alongside Assange for the new

“crime” of publishing any documents that the U.S. Government has decreed should

not be published. When it comes to press freedom threats, such an indictment

would not be in the same universe as name-calling tweets by Trump directed at

various TV personalities.

When it came to denouncing due

process denials and the use of torture at Guantanamo, it was not difficult for

journalists to set aside their personal dislike for Al Qaeda sympathizers to

denounce the dangers of those human rights and legal abuses. When it comes to

free speech assaults, journalists are able to set aside their personal contempt

for a person’s opinions to oppose the precedent that the government can punish

people for expressing noxious ideas.

It should not be this difficult for

journalists to set aside their personal emotions about Assange to recognize the

profound dangers – not just to press freedoms but to themselves – if the U.S.

Government succeeds in keeping Assange imprisoned for years to come, all due to

its attempts to prosecute him for publishing classified or stolen documents.

That seems the highly likely scenario once Ecuador hands over Assange to the

U.K.

We depend on the support of readers

like you to help keep our nonprofit newsroom strong and independent. Join Us

CONTACT THE AUTHOR:

No comments:

Post a Comment