THE GLOBAL BLUEPRINT FOR NEO-OTTOMANISM: ENERGY AND MILITARY: PART II

Source: Pixabay

02.03.2017

Issues of regional

geo-economy

Energy Imperatives

Concept:

Turkey, especially under Erdogan, is striving to achieve maximum

flexibility in its foreign policy dealings, but this is impossible to do unless

it can attain reliable and secure access to energy. Truth be told, Turkey

already has this with Russia so it doesn’t need to look any further to attain

this, but what the Neo-Ottomans want is to one day diversify their supplies

from Russia to the point where Moscow’s energy connection with Ankara is

completely depoliticized and absolutely incapable of influencing the de-facto

Caliph. This push for full strategic sovereignty is very much like what China

is currently doing through its management of multiple energy suppliers all

across the world in order to avoid a dependence on any single one. For example,

the People’s Republic counts its main energy partners as being Russia,

Turkmenistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Angola, and there’s nothing stopping

Turkey from doing something similar, albeit with some different

suppliers.

The Russian Projects:

Turkey is very comfortable

with its reliable and secure energy access from Russia, as manifested by the

current Blue Stream and future Balkan/Turkish Stream projects, and any

diversification away from its present and medium-term dependence on Russian

supplies shouldn’t necessarily be seen as a hostile act against Moscow, let

alone one which puts either of those two initiatives in jeopardy. Turkey needs

the Balkan/Turkish Stream for geostrategic reasons just as much as Russia does,

since this creates the structural platform for Moscow and Ankara’s

collaboration in solving the three most pressing

Balkan problems – Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia. Each of these

potential (continuation) conflicts are interconnected to a large strategic

degree owing to the nature of Balkan geopolitics, the demographics involved,

and the influence of traditional Great Powers such as Russia, Turkey, and

Germany, to say nothing of the interfering role that the US has recently begun

to play in this region since the end of the Old Cold War. The deteriorating

relations between Turkey and Germany give Russia an opportunity to replace

Berlin as Ankara’s partner in the Balkans and herald in a new era of

cooperative relations that would seek to resolve the three previously mentioned

trigger points which also endanger the viability of their Balkan/Turkish Stream

joint project.

In a nutshell, Balkan/Turkish Stream was agreed to by Turkey not just as

a means of securing reliable access to energy, but as a way to deepen its

strategic partnership with Russia and hopefully move it in the direction of

Balkan cooperation.

This is why the project will remain important to Erdogan and whoever may

eventually succeed him because it moves beyond the pragmatic purpose of

satisfying Turkey’s energy needs by also giving the country the chance to

promote the soft and political power of Neo-Ottomanism, though not necessarily

in a manner which obstructs Russia’s regional interests. Therefore, Balkan/Turkish

Stream will remain influential even if the Neo-Ottoman state succeeds in

diversifying its energy partners away from Russia and lessening the leverage

which Moscow is theoretically capable of exerting on Ankara due to its

dependence on the former’s resources. However, it should be forewarned that

Turkey’s efforts to achieve maximum strategic flexibility through energy

diversification could also backfire by emboldening its leadership to possibly

take geopolitical positions in the Balkans and Mideast which are contrary to

Russia’s out of the knowledge that Moscow would be less effective at possibly

wielding the energy card as it could have done before.

The Near Abroad:

Turkey’s “Near Abroad”, or in other words, the countries within close

proximity to its borders, provides for Ankara’s ideal solution in lessening its

dependence on Russian resources, and it’s already pursing these opportunities

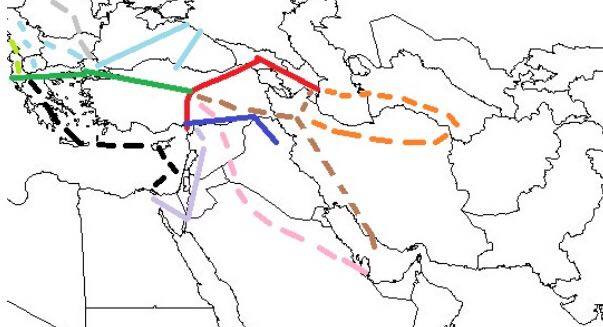

to a large extent. The map below outlines the current and forecasted pipelines

which involve Turkey to some degree or another, followed by brief explanations

of each one and their overall significance:

Light Blue – Blue Stream

(existing) and Balkan/Turkish Stream (in progress)

These projects were already described, and the hashed lines indicate the

two paths that Balkan/Turkish Stream could take in supplying the regional and

larger European market. These are essentially a revival of the South Stream

project through Bulgaria and then on towards Serbia and deeper into Europe, or

a circuitous detour through Greece and then the Republic of Macedonia before

reaching Serbia.

Red – BTC Pipeline

This existing pipeline connects Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, and is

also used to supply “Israel”. It forms the ‘spine’ of most of the planned or

forecasted routes which run through Turkey and was proof of the concept that

the country could serve as an energy bridge between various players.

Green – TANAP/TAP (in

progress)

The Trans-Anatolian Pipeline is currently being built, and it plans to

transform into the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline by crossing that sea and eventually

connecting Italy with Azerbaijan by means of Georgia, Turkey, Greece, and

Albania. This project, and any related non-Russian one in this part of the

world, is referred to as being part of the EU’s so-called “Southern

Corridor”.

Dark Blue – Kirkuk-Ceyhan

Pipeline

This Iraq-Turkey pipeline passes through the Kurdish Regional Government

and has the potential for further expansion and use. It doesn’t just have to

stop at Ceyhan, and could conceivably be expanded to connect to TANAP and

thenceforth directly to the EU market through either Italy or the Nabucco

Pipeline.

Grey – Nabucco Pipeline

This long-discussed route would in theory link Turkey with the EU by

means of the bloc’s Balkan states of Bulgaria and Romania. It largely fell out

of discussion after Russia unveiled South Stream and seamlessly replaced it

with Balkan/Turkish Stream, but it still remains a possibility, especially if

enough energy from Azerbaijan, Iraq (including the Kurdish Regional

Government), Iran, and/or possibly even Turkmenistan and Qatar becomes

available.

Brown – Iran-Turkey Pipeline

The changing geopolitical

conditions of renewed US-Iranian tensions make this route less likely than it

was before, but even so, it deserves to be spoken about at least briefly. Iran

could potentially connect its Persian Gulf energy supplies to either TANAP by

means of Southeastern Turkey (“Turkish Kurdistan”) or indirectly through

Azerbaijan and then Georgia. The first route is much more economically

feasible, but runs the high risk of being targeted by the PKK, hence the

possible need to detour through Azerbaijan and Georgia, or maybe even Armenia and Georgia in reaching the Black

Sea, Romania, and the rest of the EU.

Orange – Turkmenistan

Interconnection

The Central Asian Republic has copious amounts of gas, and it’s always

been one of the EU’s dreams to find a way to tap into it. Two possibilities

exist; an undersea pipeline to Azerbaijan and TANAP, or an overland one through

Iran. Both ideas seem unlikely to reach fruition anytime soon owing to the

unresolved territorial settlement over the Caspian Sea and increasing

US-Iranian tensions, respectively, but regardless, these possibilities

shouldn’t be completely forgotten about and opportunities might arise in the

future for their fulfillment.

Pink – Qatar-Turkey Pipeline

This route was one of the reasons behind the War on Syria, as President

Assad didn’t agree to it and opted instead for the Friendship Pipeline between

Iran, Iraq, and Syria. In the event that he’s removed through a phased regime

change in accordance with whatever conflict resolution settlement might be

agreed to, or if Syria is “federalized” (internally partitioned), then there’s

a very real chance that this project could receive a second breath of life and

be built through “Sunnistan”. Just like the prospective Iran-Turkey pipeline,

the idea is to eventually link it up with TANAP and then Nabucco in order to

supply the EU.

Lavender – Arab Gas Pipeline

There’s already a little-known pipeline bringing together Egypt, Jordan,

and Syria, and the possibility theoretically exists for it to be expanded to

Turkey too, but the War on Syria and Cairo’s post-Muslim Brotherhood problems

with Ankara have precluded this from happening for the time being. If President

Assad is removed and Egypt and Turkey reconcile, then this project might become

viable and contribute additional energy supplies to Turkey, as well as

potentially feed into Nabucco.

Black – Eastern

Mediterranean Pipeline

The last examined project

which Turkey has its sights set on is the large-scale one which has been proposed for linking “Israel’s”

Leviathan offshore gas fields with Cyprus’ nearby Aphrodite one via an

underwater pipeline that would eventually terminate in Greece, possibly with

the chance of joining TAP to supply the southern EU. It also can’t be precluded

that this project would connect with the proposed Ionian-Adriatic Pipeline

between Greece, Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia, and Croatia in sending energy to

Central Europe. In order for Turkey to have a stake in this project, it needs

to succeed in pressuring Nicosia to agree to the federalization of Cyprus and therefore allowing

the northern Turkish-controlled part to indirectly enable Ankara’s

involvement.

Light Green –

Ionian-Adriatic Pipeline

Referred to above, this prospective pipeline would either serve as a

branch of TANAP or the other half of the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline.

Distant Finds:

Other than the many energy connectivity possibilities which exist in

Turkey’s Near Abroad, there are also three other suppliers which have yet to be

discussed, and these are Libya, Tanzania, and Mozambique.

Libya

The North African state is

mired in an intense state of civil war after the pro-Turkish Muslim Brotherhood

“rebels” were unsuccessful in cementing their power following the overthrow and

murder of former Libyan leader Gaddafi. There doesn’t seem to be much hope that

Turkey can restore what it had assumed would have been its premier position in

the country after the “Arab Spring” events, even though there have been reports

that it’s still trying to do so through low-scale support given to various

militias. Even in the case that Ankara can recover some of its strategic losses

in the post-Gaddafi country, it wouldn’t be with the intent of building a

pipeline of any sorts, but rather through controlling some of Libya’s energy

exports to Europe via its companies. However, this is looking increasingly

unlikely as Western and Russian companies are racing

to fill the void in preparing their business plans for whenever the country

eventually stabilizes

Tanzania and Mozambique

These two gas-rich countries

have yet to become major global players on the energy marketplace, but their

offshore deposits are impressive enough that they’re expected to reach this

enviable position sometime in the future. Just like with Libya, Turkey harbors

no desire to build a pipeline from either Tanzania or Mozambique to its own shores (nor

is such an idea economically feasible), but wants to simply secure reliable

access to the energy that’s expected to be exported from here in the next

decade. This forward-thinking planning was one of the reasons why Erdogan visited these two countries in

January, and it’s expected that the relationship between all three parties is

only expected to grow in the future. Keeping in mind that other Great Powers

are racing to tap into these resources too, it’s a prudent move for Turkey to

try to get in first and possibly play the ‘caliphate card’ in appealing to

Tanzania’s majority-Muslim population and minority believers in

Mozambique.

Military Maneuvering

Part I mentioned that there’s an almost perfect overlap between Turkey’s

Neo-Ottoman soft power, geopolitical, energy, and military interests, so it’s

now appropriate to explain the latter element of Erdogan’s global blueprint and

prove how it closely corresponds with everything that’s been expostulated upon

to this point. The most coherent way to do illustrate the undeniably visible

pattern at play is to go through the previous list of energy interests and

highlight the influence that Turkey’s military is playing on each of these

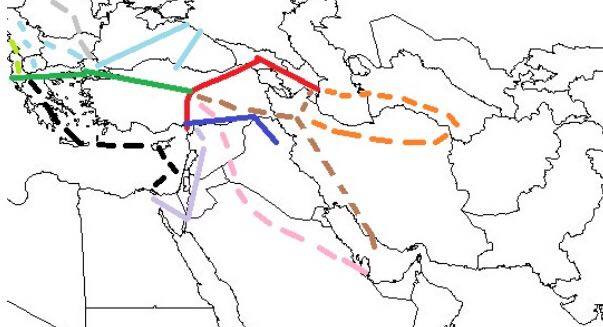

actual, ongoing, and prospective projects. For comparison’s sake, here’s the map

once more, and it will be followed by the exact same descriptive format for

outlining each endeavor and then explaining how the relevant involvement of

Turkey’s military is conditioned on achieving Erdogan’s grand Neo-Ottoman

objectives of positioning his country into a strategic superpower:

Light Blue – Blue Stream

(existing) and Balkan/Turkish Stream (in progress):

Turkey didn’t have to use any military means to secure either of these

projects, but Russian-Turkish military coordination in Syria and pertinent

conflict resolution diplomacy in Astana have strengthened the bilateral

relationship and confirmed the broader strategic wisdom behind agreeing to both

of them.

Red – BTC Pipeline:

Turkey has fraternal

relations with Azerbaijan and has been blockading its rival Armenia – whom

Turkey also has issues with concerning the post-World War I genocide – and has

been supplying Baku with military hardware and advisors ever since the

country’s independence. Ankara is also a strong proponent of Georgia’s NATO

membership, not so much as a means of irritating Russia, but as a way to

advance Turkey’s influence over the Caucasian country and pair the energy

relationship with a military one in recreating a regional sphere of influence

in the transcontinental border space.

Green – TANAP/TAP (in

progress):

Relations are horrible right

now between Turkey and Greece, though they’re very good between Albania and

Turkey. Whether or not it’s connected, ties between Tirana and Athens – never close by any means – have

gotten slightly worse around the same time

as those between Ankara and Athens have, though for different reasons, albeit

both related to territorial disputes. Greece, however, isn’t recognized by any

serious experts at this time as exhibiting the behavior of a sovereign and

independent state, so it’s possible that its EU overseers might force it to

remain on good enough terms with both of its Neo-Ottoman neighbors in order to

not jeopardize the prospects for the many “Southern Corridor” projects which

are anticipated to run through its territory.

Dark Blue – Kirkuk-Ceyhan

Pipeline:

Turkey is very close to the

Kurdish Regional Government of Masoud Barzani, who despite being a Kurd, bucks

the Mainstream Media stereotype by enjoying high-level strategic relations with

Erdogan. In fact, relations between both actors are of such an important level

that Barzani ‘invited’ Turkish troops into the

areas of Northern Iraq that he controls in order to train the Peshmerga and

defend against any of Daesh’s possible offensives further north.

This sparked a major diplomatic incident in December 2015, but looking

past the problems that it caused for Ankara and Baghdad, it ironically showcased

just how close Erbil and Ankara are, contrary to popular thought.

As it pertains to the examined pipeline politics at play for

Neo-Ottomanism, this proves that Turkey is willing to dispatch military forces

to protect the Kirkuk-Ceyhan route and would also likely be favorable – or at

the least, not outright opposed – to “Kurdish independence” in Northern Iraq,

so long as Barzani and his Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) remained in charge

and the resources kept flowing through Turkey en route to the global

marketplace.

Grey – Nabucco Pipeline:

Turkey hasn’t utilized its military to promote this proposed project

because it simply sees no need to. That, however, doesn’t mean that Turkish

military deployments elsewhere aren’t related to this pipeline, since Ankara’s

moves in Northern Iraq and Southeastern Turkey (“Turkish Kurdistan”) are

directly connected with potentially securing these routes for future use and

thereby enabling their eventual linkage with Nabucco one day.

Brown – Iran-Turkey

Pipeline:

As was just mentioned above,

Turkey’s military operations in its southeastern corner of the country

(“Turkish Kurdistan”) are partially meant to destroy the PKK terrorist

insurgency with the intent of facilitating a possible Iran-Turkey pipeline

which could eventually feed Europe through Nabucco. It should be noted,

however, that amidst the recurrence of traditional

Turkish-Iranian suspicions (in spite of the Tripartite between them and

Russia over Syria) and rising US-Iranian tensions, this pipeline seems ever

less likely to be built anytime in the future, and that Turkey’s military

actions in the southeast are mostly for the sake of national unity and to

promote a possible forthcoming federal solution which would help propel the

administrative-political expansion of Neo-Ottomanism with time.

Orange – Turkmenistan

Interconnection:

There is nothing that Turkey can do militarily to improve the chance that

this project is ever actualized , but its alliance with Azerbaijan and anti-PKK

efforts in the southeast of its own territory help to secure it in the

unlikely event that it’s ever constructed.

Pink – Qatar-Turkey

Pipeline:

President Assad’s choice to decline participation in this project is

perhaps one of the main triggers for the War on Syria, and it’s why Turkey has

expended such time, energy, and resources towards trying to topple him. It also

explains why Turkey both actively and passively assisted terrorist groups

involved in this campaign, whether through arming them directly or turning a

blind eye through their transit across its territory.

Operation Euphrates Shield has as one of its

unstated objectives the creation of a pro-Turkish sphere of

influence in the north which could eventually be expanded to include all of

“Syrian Kurdistan” (should a KDP-like pro-Turkish party be successfully

installed there) and the southern desert regions of “Sunnistan” (including

potentially those in western Iraq as well).

Moreover, Turkey opened up a military base in

Qatar last year, which presently serves the function of deepening the Muslim

Brotherhood bonds between the two countries and also supervising part of the

maritime route through which Qatari resources will travel on the way to Turkey,

which will likely see much use in the coming future seeing as how the chances

for a Qatar-Turkey pipeline are plummeting unless Syria can be coerced into

agreeing to de-facto “federalization” to facilitate it.

Lavender – Arab Gas

Pipeline:

The prospects for this pipeline are fully connected with whether or not

President Assad is deposed and if Cairo and Ankara enter into a rapprochement.

Ties between Egypt and Turkey have been strained ever since President Sisi

overthrew pro-Turkish Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi in 2013, and

they’ve struggled to return back to their prior level ever since then. Even so,

there’s nothing in principle which precludes Egypt and Turkey from cooperating

on the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline since they both also ‘recognize’

“Israel”.

Black – Eastern

Mediterranean Pipeline:

One of the most ambitious energy projects in the future stands to be the

Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline, and it’s probably one of the reasons why Turkey

decided to publicly reconcile with “Israel” after the 2010 Gaza flotilla

incident. Turkey doesn’t directly have any stake in this initiative, but it

does have a chance to get involved via its client ‘state’ of Northern Cyprus,

specifically if this entity enters into a federal arrangement with the rest of

Cyprus which could give it and its decision makers access to the offshore

Aphrodite deposit.

This in turn would essentially give Turkey a channel through which it

could also profit from this project, but more importantly, become a strategic

overseer over a crucial transit section of it (via a federalized settlement to

the Cyprus conflict and the North’s corresponding influence on the united

entity’s economic policy), thereby propelling Turkish influence to even higher

levels than previously thought possible. Ankara would then be able to have yet

another form of leverage over Athens which could complement TANAP and possibly

lead to Greek concessions in the Aegean Islands dispute sometime in the

future.

Libya:

Turkey lost almost all of

the influence that it thought it had gained following the overthrow and killing

of Gaddafi after Libya slid into a multisided civil war, and Ankara has yet to

claw back even a fraction of it despite its reported assistance to some of the armed

groups (Neo-Ottoman proxies) there. Erdogan triumphantly strutted across the three

post-“Arab Spring” North African states of Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia at the end

of 2011, but in the years since, Turkey’s influence has considerably diminished

over each one of them, except perhaps strategically irrelevant (in this specific

context) Tunisia.

The US’ hopes for achieving a transregional Muslim Brotherhood series of

pro-Turkish satellite states failed miserably after the Syrian people refused

to surrender and Libya consequently slid into civil war. The 2013 Egyptian coup

spelled the final end of this geopolitical project, at least in its originally

intended iteration, though it might receive a late boost of sorts if aging

Algerian President Bouteflika passes away and a second Islamist Civil War

breaks out in the sprawling North African country.

However, even in such a case, the close proximity to Europe and very high

likelihood of uncontrollable immigration flows portends a rapid reaction

intervention by the Western Great Powers (led by France) in order to stem the

predictable chaos, which would probably work against Turkish Neo-Ottoman

strategic interests. Correspondingly, the resolution of the Libyan Civil War

probably won’t be to Turkey’s benefit since Western and even Russian companies

are poised to gain influence over the country’s energy exports and squeeze out

Turkey.

Tanzania and Mozambique:

The North African obstacles

interfering with Turkey’s Neo-Ottoman global blueprint aren’t present in

Southeast Africa, though, which is why this region of the world is so promising

for Ankara when it comes to securing reliable energy access. Erdogan and his

team seem to have already realized this, which might be why Turkey is opening up a military base in

the Somali capital of Mogadishu. This isn’t just to fight against Al Shabaab

like the press releases make it sound, but to also eventually exercise

influence along the north-south maritime route which will become ever more

important as Turkey seeks to diversify its dependence on Russian resources by

becoming a larger purchaser of Tanzania and Mozambique’s.

On a broader level,

Sub-Saharan African offers enormous market and agricultural potential for

Turkey, and Ankara’s diplomatic offensive of the past years in

opening more embassies and consulates all across the continent, as well as

Turkey’s improved flight connectivity to dozens of cities, improves the odds

that this will reap profitable future dividends. There’s also the fact that

nearly a quarter of all the world’s Muslims live in Africa, where they

constitute nearly half of the population, which plays into Turkey’s Neo-Ottoman

Caliphate narrative by improving the soft power image that it has in eyes of

some co-confessionals. Taken even further, it’s possible that Turkey’s military

inroads with Somalia and its strategic ones with Tanzania and Mozambique might

serve as springboards for further Great Power expansion deeper into the

continent.

(Continued in Part III).

______

All personal views are my

own and do not necessarily coincide with the positions of my employer (Sputnik

News) or partners unless explicitly and unambiguously stated otherwise by them.

I write in a private capacity unrepresentative of anything and anyone except

for my own personal views. Nothing written by me should ever be conflated with

Sputnik or the Russian government's official position on any issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment