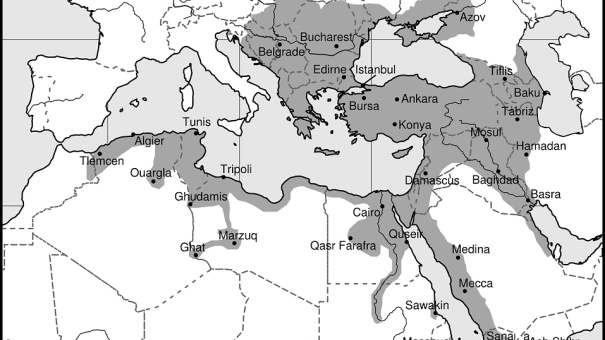

Ottoman Empire. Source:

Pixabay.

01.03.2017

Neo-Ottomanism is the

driving ideology behind contemporary Turkey’s domestic and foreign behavior

It’s no secret that

Turkey endeavors to restore its Great Power status all across its former

Ottoman realm, driven in part by the strategic calculations outlined by former Foreign and Prime Minister Ahmet

Davutoglu and carried through to its present iteration through the pioneering

charisma of President Erdogan. The policy of so-called “Neo-Ottomanism”, as

it’s been popularly referred to by outside commentators over the years, has

proven itself to be one of the most disruptive ideologies of the 21st century.

Supporters laud its ambitious vision to return Turkey back to its Ottoman roots

– both in terms of de-facto religiously influenced governance and Great Power

status – while detractors point to the death and destruction that

Neo-Ottomanism has directly contributed to in Syria as evidence that it’s

resulted in much more harm than good.

No matter which side of the debate one stands on, it

can generally be agreed that Neo-Ottomanism is the driving ideology behind

contemporary Turkey’s domestic and foreign behavior, and that it’s indeed one

of the most influential forces shaping the future of the Mideast, for better or

for worse. That being said, it’s absolutely important to understand the nature

of this grand strategy in order to accurately forecast its development across

the coming years, hence the reason for conducting this research.

The author argues in Part

I that Neo-Ottomanism relies on soft power nostalgia for the Ottoman past,

emphasizing Turkey’s central role in building what would eventually become the

world’s largest caliphate, albeit modified in political-administrative ways to

adapt for the present post-modern/post-Western reality. In its quest to de-facto recreate the

Ottoman Caliphate, Turkey is transforming its internal governing structure in

order to ultimately make it more suitable for expanding and retaining its

foreign influence. Pertaining to the latter, the transnational Muslim

Brotherhood network which is clandestinely embedded across all levels of

society in the Mideast and North Africa (MENA) acts as the vanguard

‘revolutionary’ force for Neo-Ottomanism, but given its recent setbacks over

the years, it’s insufficient for sustaining Turkish influence across this large

region.

Therefore, Turkey is simultaneously pursuing a

broad-based strategy to secure as many reliable sources of energy as possible

in order to position itself as a more independent player unencumbered by the

structural restraints which come from its present dependence on Russian

resources, which occupies the focus of Part II. As it turns out to be, there’s

almost a perfect overlap between the soft power, geopolitical, energy, and

military components of Neo-Ottomanism, and this second section endeavors to

shed light on these connections in order to imbue the reader with a more

comprehensive understanding of this Great Power project. In order to present a

more comprehensive level of analysis, Part III then briefly examines the

opportunities and challenges that Turkey faces on its path to build the

Neo-Ottoman Caliphate.

Soft Power Underpinnings

Historical Memory:

Neo-Ottomanism builds off of the historical memory of

the Ottoman Caliphate, a period of time which has become very popular to

reminisce about in Turkish society and which also has its fair share of

admirers among some of the more religiously focused Arabs all throughout MENA.

While some people such as the Syrians, especially the secular ones, view the

Ottoman centuries as almost half a millennium of occupation (just like their

Serbian counterparts do in the Balkans), there are still many others which interpret

it very differently and see it as a high point in their history. These very

religious individuals are much more loyal to the concept of the Ummah –

especially its political-administrative embodiment as the former Turkish-led

Ottoman Caliphate – than they are to their respective countries, and it’s from

this large proportion of the masses that Erdogan seeks to cull his

international supporters.

The Muslim Brotherhood Alliance:

By and large, however, there are still many populists

which have strong reservations about the nature of Turkish rule over the

centuries and could easily stir up trouble which could undermine Ankara’s

ambitions, which is why it’s so important for Turkey to differentiate between

its ethno-nationalist identity as an ‘exclusive’ country of the Turks and its

inclusive religious one as a fellow “brother” to all the Muslims in the world.

Seen in this way, then Erdogan’s decision to openly sympathize with and support

the Muslim Brotherhood takes on a different meaning, since it can thus be

understood as constituting part of his religious opening to MENA and

demonstrating his common point of convergence with non-Turkish Muslims. This

group isn’t representative of the majority of Muslims in this transregional

space, but it’s nonetheless a powerful anti-government force to be reckoned

with, and additionally gives Erdogan and Turkey added ‘credence’ among

religious conservatives.

What’s crucial to

understand about the Muslim Brotherhood is that it aspires to overthrow both

secular and Wahhabi governments in order to usher in its own form of Islamic

governance. This technically makes it a ‘revolutionary’ organization, and it in

many ways structurally functions as a 21st-century iteration of the

communist party in the sense of wanting to replace the present political order

in their country with a new transnational one unified by ideology. The “Arab

Spring” Color Revolutions can thus be analyzed as an attempt to carry out a swift

succession of coups designed to lay the political-ideological foundation for a

network of satellite states which would be run by whichever power had the

highest degree of influence over the Muslim Brotherhood. While this role was

originally played by Qatar, the tiny monarchy’s leadership capabilities are

understandably limited and it has no history of ruling the region, whereas

Muslim Brotherhood-aligned Turkey has centuries’ worth of experience in

managing the Ottoman Caliphate.

From the geopolitical perspective, the US sought to

replace the existing order in the Mideast with a Turkish-controlled network of

Muslim Brotherhood-run states, essentially recreating the Ottoman Caliphate in

order to both organize a partial pan-Arab Sunni alliance against Shiite Iran

and exert pressure on Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Kingdoms, considering of course

how deathly afraid the latter category are that the organization could one day

violently come to power there too.

This strand of thinking correlates with the

integrational tendencies observed elsewhere in the world, be it the EU, the

Eurasian Union, SCO, or ASEAN, except furthered in a much more disruptive,

violent, and sudden manner.

It also was

preconditioned on having Turkey behave as the US’ “Lead From Behind” partner in controlling this region as Washington’s

proxy, relying on Erdogan’s comparatively more ‘authentic’ Muslim credentials

compared to the American President’s in order to earn him added ‘legitimacy’

among these populations in justifying his envisaged transnational leadership

role as this ideology’s most influential state patron. For as ideal as this

strategy sounded on paper, however, it didn’t deliver as expected in practice

and for reasons which will be touched upon later on in the text. Nevertheless,

Turkey remains tied to the Muslim Brotherhood and utilizes it as its

Neo-Ottoman vehicle for advancing Ankara’s influence all across MENA, even if

it never has the opportunity to do so on as grand of a basis as it was poised

to immediately after the ‘success’ of the “Arab Spring” Color Revolutions and

by the time of Erdogan’s late-2011 ‘victory tour’ of North Africa.

Standing Apart From The Saudis:

For as impressive of an

historical legacy as it has, and given the relative effectiveness of its Muslim

Brotherhood foot soldiers, Turkey still doesn’t hold the same amount of sway

over MENA and the rest of the global Ummah as Saudi Arabia does. The Saudi King

is recognized as the caretaker of the Two Holy Mosques, and this alone imbues

him with enormous respect all across the Muslim world. The Kingdom’s support of

Wahhabism has also earned it many influential adherents among the Ummah,

despite this strand of Islam being largely recognized by many Muslims as being

ultra-conservative and even radical. In fact, an under-reported gathering in

Chechnya last year saw

Sunni religious leaders from a host of countries all but ‘excommunicating’ (to

use a Catholic comparison) the Wahhabis from their fold, further highlighting

the general unattractiveness of this ‘brand’. Be that as it may, it’s hard to

argue with the assertion that Saudi Arabia’s global influence is predicated on

the dual pedestals of its caretaker role over the Two Holy Mosques and the

ideology of Wahhabism, the latter of which has been given a surreal soft power

boost due to the hundreds of billions of petrodollars that stand behind it

decades-long proselytization campaigns.

he value-added differentiator that sets Turkey apart

from Saudi Arabia is its historical legacy of administrative-political

leadership over a broad part of the Ummah and its embrace of the relatively

(key word) more moderate Islamic governance as advocated by the Muslim

Brotherhood. Although there are in practice very little differences between

these two, the perception of course is that the Muslim Brotherhood is slightly

less radical than the Wahhabis, which theoretically gives Turkey a soft power

boost over the Saudis.

Additionally, the reason why Saudi Arabia has listed

the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization – other than its objectively

identified use of terrorism in pursuit of its goals – is that the group wants

to replace the King as the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques. Extrapolating

from this and going forward with the scenario, the organization’s most powerful

foreign patron would thus become the true caretaker of these religious sites,

and should this continue to be Erdogan and the Turkish state, then it would

dramatically elevate them to becoming the symbolic leaders of many of the

Ummah’s Muslims.

There’s no evidence that

Turkey is conspiring against Saudi Arabia and directly working with the Muslim

Brotherhood to overthrow the King, but in the event that this group does indeed

succeed with its ‘revolutionary’ goal, then it would instantly propel Erdogan

to becoming a 21st-century Caliph ruling over a

post-modern/post-Western Neo-Ottoman Empire at the crossroads of Afro-Eurasia,

thereby granting him unprecedented geopolitical influence over global affairs.

Though it’s extremely doubtful that this will ever happen, let alone anytime

soon, this idea can be said to serve as an inspiration which works towards

Turkey’s ultimate soft power favor in recruiting more Arab MENA Muslims to its

Neo-Ottoman cause. More than likely, any advancement of this scenario wouldn’t

necessarily be due to Turkish cunning, but rather the Muslim Brotherhood’s

typical exploitation of chaotic situations, such as in the event that domestic

destabilization arises within the crumbling Kingdom and is first exacerbated by

Iranian (political, diplomatic, or perhaps even other) support for its Shia

co-confessionals in the oil-rich Eastern Province, which then provides space

for the Muslim Brotherhood to rise elsewhere in the country and try to pull off

an Egyptian-like coup against the government.

Administrative-Political

Tweaking

The soft power

underpinnings of Neo-Ottomanism might sound attractive to a broad base of MENA

Muslims, which could naturally give Turkey an enormous amount of geopolitical

sway, but they’re incapable by themselves of ensuring that Ankara’s influence

remains enduring and ever-lasting in the manner that Erdogan expects it to be.

It’s conceivable that Turkey could one day influence Muslim

Brotherhood-governed countries all across this transregional space along the

lines of the abovementioned “Lead From Behind” strategy, but this is crucially

dependent on the stability of the Turkish state itself and its immediate borderlands.

Turkey and its two southern neighbors have been greatly destabilized owing to

Erdogan’s front-row participation in the US’ War on Syria, which has revealed

itself as being a 21st-century iteration of the Yinon Plan in

respect to dividing the Muslims all along “Israel’s” periphery. Even though

that’s how it’s turned out, it was thought at the time by Erdogan that this was

his perfect opportunity to establish a Muslim Brotherhood client state next to

his borders and therefore give him a prime position to project more ideological

influence into the Arab World. It would also, of course, enable the

construction of the Qatar-Turkey pipeline which President Assad had earlier

rejected, the significance of which will be elaborated on later.

While the War on Syria is

proving itself to be a failed enterprise for all of its culprits, especially

Turkey, it also saw the eventual administrative-political tweaking of

Neo-Ottomanism. Turkish scholar Dr. Can Erimtan warned in late-2013 that “the government’s long-term

goal (as arguably expressed in the AKP’s policy statement Hedef 2023) is to

transform the nation state Turkey into an Anatolian federation of Muslim

ethnicities, possibly linked to a revived caliphate. In this way, Turkey’s

future (as a nation state) would arguably become subject to Anatolia’s past as

a home to many different Muslims of divergent ethnic background.” What this

basically means is that the devolution of the unitary Turkish state to a

federation would give Ankara the flexibility to incorporate/annex territories

under its wing which are populated by people of a separate ethno-nationalist

identity in order to build the post-modern/post-Western 21st-century

Neo-Ottoman Caliphate. In practice, this could allow for all or part of Syria

become part of a reformatted Turkey, as well as Syrian and Iraqi “Kurdistan”,

and the geographically large Sunni areas of Iraq. In fact, the “federalization” of both Syria and

Iraq would amount

to an internal partition in both cases and the emergence of a transnational

sub-state “Sunnistan” which could, under Dr. Erimtan’s analyzed template of the

future Turkish state, come under Ankara’s eventual control.

Turkey is still a unitary

republic, but it’s on the verge of transforming into a centralized one if the

forthcoming constitutional amendments are approved in April’s referendum. Erdogan would in that case be empowered to reverse

Ataturk’s legacy by removing secularity from the country’s constitution, or at

the very least overriding it for all intents and purposes. The devolution into

a federalized republic could also be sold to the country’s citizens as a

compromise with the Kurds, though in reality it would be a sly maneuver for one

day formalizing the inclusion of Syrian-Iraqi “Kurdistan” and “Sunnistan” into

the Neo-Ottoman Caliphate. If an expanded Turkey (or whatever it might be

called by that point) can directly connect to Jordan and Saudi Arabia, then it

would establish itself as a major global power capable of both cooperating and

competing with its southern neighbors. Either way, it would earn a lot of

“respect” among its supporters in the Ummah, particularly those which used to

be a part of the original Ottoman Empire. For this to happen, though, like it

was earlier written, Turkey needs to devolve from a unitary state to a

federalized one, whether or not it still maintains (even in a superficial

sense) its republican identity, as this would enable it to more easily absorb

more Muslim Brotherhood-controlled territories and supporters.

(Continued in Part II)

__________

All personal views are my

own and do not necessarily coincide with the positions of my employer

(Sputnik News) or partners unless explicitly and unambiguously stated

otherwise by them. I write in a private capacity unrepresentative of

anything and anyone except for my own personal views. Nothing written by

me should ever be conflated with Sputnik or the Russian government's

official position on any issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment